For Canadians with asthma, catching their breath can be an ongoing struggle as they cope with a disease they can’t even see. But researchers are developing a new way to give patients a full picture of their disease, so their doctors can find the treatment that works best for them and helps them breathe easier.

As many as 3 million Canadians have asthma. The disease makes it difficult to breathe because of two abnormalities: airway inflammation and something called “airway smooth muscle dysfunction,” which causes airways to close up in response to environmental triggers, such as smog.

These two abnormalities often occur together, but some patients have flare-ups triggered by one or the other of these conditions. It is important to know which component is causing problems for a patient, because each is treated with different medications.

Many patients, like Donna Hesch, struggle to control their condition because don’t realize how severe it is. Hesch says in her 20s, she often would get short of breath but she had trouble believing she had asthma.

Hesch, 56, recently learned the extent of her condition when she took part in research led by Western University researchers looking at a new asthma imaging method.

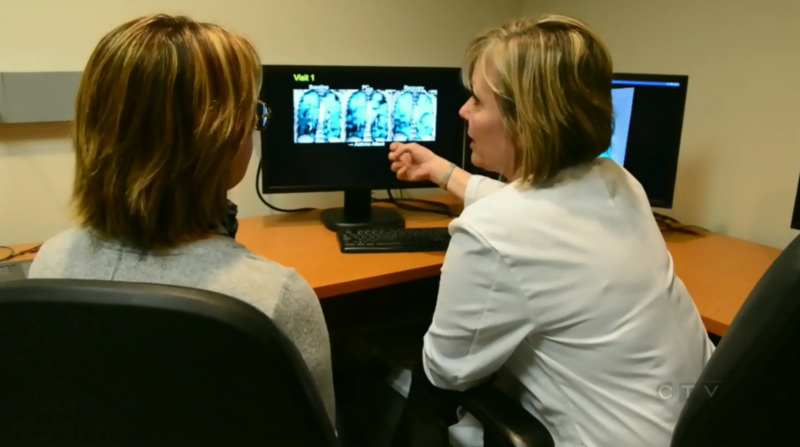

That research led to a study published this week involving 27 asthma patients who had to breathe in a gas that acts as a contrast agent during an MRI of their chest,. The idea was to get a picture about how much of their lungs were or weren’t being used. Hesch was stunned by what she saw on her own scan.

“There were a lot of spots that no air was getting at. It kind of blew me away,” she said in an interview with CTV News. “…I guess I didn’t realize at there were so many spaces that were not getting any air. It was surprising.”

Grace Parraga, who researches medical imaging at Western’s Robarts Research Institute, says that in people with healthy lungs, the gas moves throughout the lung. Those with asthma get “ventilation defects” – areas where air can’t reach. Such defects are indications those areas are inflamed or not working properly.

Parraga says even she was surprised by how the MRI-gas scan helped paint a picture of a patient’s disease.

“I had to so this imaging over and over again in patients before I really believed what I was seeing,” she said. She said the images helped explain why certain treatments were not working for certain patients.

“Now, we had something we could see that could relate back to how a patient was feeling,” she said

Knowing what kind of dysfunction affects a patient can help guide physicians and respirologists as they choose treatments, including the new and more expensive personalized therapies, such as injectable monoclonal antibodies.

“So this is an exciting new tool that will help us see where the air is going, get a handle on the reason why the air isnot going into certain parts of the lungs. and use new therapies to fix those problems,” said Dr. Parameswaran Nair, a professor of Medicine at McMaster University and respirologist at the St. Joseph’s Firestone Institute, which was part of the study.

Doctors typically use spit, or sputum, tests to identify airway inflammation. Parraga says her team’s results suggest that both sputum analysis and MRI can pinpoint the source of poor asthma control, “which could simplify therapy decision making.”

For Hesch, the images helped her understand why she needed to take her illness seriously.

“I think I realized that I really had to take care of myself. Before that, I had a few bad chest colds and got pretty sick… But when I saw those, I think I realized that I really needed to take good care of myself,” she said

The study was performed on only those with the most severe asthma – those patients whose illness costs the health care system the most, Parraga says.

“It is for these patients that this kind of testing is ideal, especially when current therapies have failed and when you wish to test newly approved biologic therapies,” which she says can cost $25,000/year.

The costs of the MRI would not be high, she added, because the scan lasts only 15 seconds and the image analysis is automated. The entire test, including the contrast gas, would costs just a few hundred dollars, she estimates.

The study is published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.